Burnt Shadows by Kamila Shamsie

How much of home is made of brick and mortar and how much of family is made of blood?

In 2019 I was introduced to Kamila Shamsie’s writing when I read Home Fire. A book that has made me cry every time that I have read it (3 times since the first time I flew through the pages.) and has travelled across countries with me. One day people will ask me which books contributed to making me the person I am, the reader I am, the writer I hopefully become; and I will point to the yellowed, well-thumbed, copy.

Shamsie’s books deal with a variety of topics that I can categorise as topics she keeps returning to after now having read three books from her seven book bibliography. Burnt Shadows picks up in 1945 right before the bombing of Nagasaki and follows the cast of characters to Delhi right before the partition, Pakistan during the 90s, and concludes in a post-9/11 New York. She talks about global politics, proxy wars, immigration, racism, terrorism, and Islamophobia, with a fluency of language that does not take away from the horror of the violence, but somehow adds to the impact reading about it has. Even while I was reading her describe the mindless destruction of human life, human potential, land, entire worlds, due to the bombing of Nagasaki, I was left breathless by her imagery and use of words. Her prose is flowery; but by creating a contrast to the gruesome events she is narrating she paints an astounding picture of a world where beauty can exist even amidst gratuitous violence.

What would you stop at to help the people you love most? Well, you obviously don’t love anyone very much if your love is contingent on them always staying the same. (Home Fire)

But at the heart of all her novels are the people. In the midst of war, she shifts focus to tender moments of love; romantic, platonic, familial, and sometimes just the brief bursts of love that one feels for a stranger. She questions what it means to be a family. In Home Fire, the most pressing question seems to be: How far can one go for family; for love? As Aneeka sits vigil with the body of her brother, facing the gaze of the world, without flinching, with ferocious protectiveness of her twin, you wonder at the limits of sibling love. Political powers from around the globe stand against her and yet, she tenderly loves her brother. How much of your love for a person is dependent on them never changing, never doing something unforgivable? Isma has spent her life caring for her twin siblings. Her life is controlled by her father’s decisions. Even her freedom is tinged with Parvaiz’s rebellion. Her first love is overshadowed by Aneeka’s beauty. In the turmoil of global politics and personal drama, there is tenderness in Shamsie’s descriptions of a Pakistani British family trying to survive when the world is pulling them apart. Death and grief are as constant themes in the book as love is; but Shamsie has the ability to balance the two. Never letting one overpower, or overshadow, the other.

Everything else you can live around, but not death. Death you have to live through. (Home Fire)

In much the same way, the central question in Burnt Shadows is: What is home? Is it a place? People? A country? Brick and mortar? And, what is family? Blood? Or the people you choose? After losing her fiancé, Konrad, and her father to the devastation of the atomic bomb (she imagines remains of the former on a rock that she buries when she finds no body, and mistakes the latter for a reptile after the toll of the bomb), Hiroko’s only aim is to move to India and meet her fiancé’s estranged sister. She is looking for any connection to the man she loved, even if it is to someone who had no relation to him anymore. A part of Hiroko is looking for home. How do you reconcile the image of home when it has been brutally transformed beyond recognition, when everything that you held dear is taken away from you there? Hiroko finds a home; however temporary, a family; however tenuous, and a second chance at love.

Yes, I know everything can disappear in a flash of light. That doesn’t make anything less valuable. (Burnt Shadows)

Her husband, Sajjad, is a man in love with the city he was born in and has lived in. Dilli, not the Delhi of the British, has inspired poetry for decades, and in the same way Sajjad idealises the narrow streets, the Islamic architecture, the worlds that exist around every corner. And through his eyes, his words, and sequestered Urdu lessons, he gets Hiroko to fall in love with the romance of the city. When a twist of fate, brought on by the violent partition of India means that Sajjad cannot return to his beloved home, his heart is broken as much as it would have been if he had lost Hiroko instead. Losing his home, his Dilli, is like losing a part of his identity. He manages to make a life and a home for his wife and son in Pakistan, but some part of him is lost forever when that tether is cut. In the same way that the scars, both emotional and metaphorical, of the bomb keep Hiroko tethered to Japan even decades after she has left home, an idealisation of the old world charm of Delhi keeps Sajjad prisoner to dreams of ‘what could have been’.

My history is your picnic ground. (Burnt Shadows)

For Sajjad the biggest failure is his inability to make his British employer see the same beauty in Delhi. He finds himself wondering how the British haven’t managed to make India home at all, as compared to the other invaders the land has endured over the centuries. He muses, “Why have the English remained too English? Throughout India's history conquerors have come from elsewhere, and all of them --- Turk, Arab, Hun, Mongol, Persian --- have become Indian. If --- when ---this Pakistan happens, those Muslims who leave Delhi, Lucknow and Hyderabad to go there, They will be leaving their homes. But when the English leave, they'll be going home.” Sajjad is ignoring Henry Burton when he says this, who later becomes the American: Harry. The child of James Burton, Sajjad’s British employer, and Elizabeth, Konrad’s sister, never knows a home other than India. To grow up believing that the land you live in is your home, that you belong there even though you look different and are treated differently, only to be told that you have to go to a strange land and be loyal to a new home, is a unique injustice. When Henry is sent to England to study in boarding school, it is another tether being pulled to its extreme. He finds it difficult to replace his idea of home; Indian summer, the musical lilt of Urdu, mangoes, and sprawling gardens; with an unfamiliar and hostile land. In that discomfiture, he is forced to create an identity for himself.

What he is unable to do in England he manages to do in New York. The most under-the-radar, but surprisingly nuanced character in the book is Elizabeth. Ashamed of her German connections, in the first half of the book she hides behind her husband’s British identity, her marriage (which was once happy but has staled since then), a life that does not suit her and makes her feel caged. Hiroko’s arrival and the surprise grief of losing a brother she didn’t know much about forces her to rethink her life. All she needs is an invitation from a cousin to leave behind any notion of home and move to the glamorous and slightly scandalous New York. Once again Shamsie cleverly blends the idea of home and identity. For Hiroko and Sajjad the conflict was building a home away from the land they called home, for Elizabeth it was always feeling like the outsider and then finally finding a home in an unlikely place. America gives her that root, and she passes it on to Henry/Harry, who takes the loyalty towards his new home one step further by joining the CIA.

For the next generation, the idea of home and identity are even more tenuous. What is home when you’re a half-Japanese and half-Indian, living in Pakistan? What is identity when you share features with the Hazaras of Afghanistan, even though you have no connection to them? Raza, Hiroko and Sajjad’s son, faces these questions as he grows up constantly at the receiving end of taunts and comments in the streets of Karachi. Shamsie’s family had to move to Karachi after the partition of India, she spent several years growing up in the bustling city. This is where the author’s home merges with the idea of home of the characters. In every sentence and description of the city the reader can see that Shamsie is finally on her home ground. If there are hints of racial stereotyping in the first half of the book (Hiroko wearing a kimono when the bomb strikes, or her father’s act of rebellion being the burning of a cherry blossom tree), there is an understanding, and innate cognisance about Pakistan, and what it means to be Pakistani in the latter. If Raza is a symbol for the dissonance of being Pakistani and not knowing who you are, Kim is the confidence of being American and living in the comfort of the American dream come true.

If the greatest loss of his life is the loss of a dream he's always known to be a dream, then he's among the fortunate ones. (Burnt Shadows)

Sometime in August I visited the Museum of the Home in London. The visit was unplanned and I remember wandering off the street and into the air-conditioned building without really knowing what I was walking into. But there was definitely some serendipity at play when I did. Born after the pandemic, the Museum of the Home poses the question: What does home mean to you? Each room of the museum tries to answer that, through carefully maintained relics of the past, ephemera borrowed from people, stories etched on every wall, knickknacks that made up homes, rooms that recreate the decor—and decorum— of homes over a century, and in one special room, recorded videos of people answering the question. There is no one answer. Home is a mixture of a lot of things, sometimes you’re born in it and sometimes you spend your whole life trying to find it. Most importantly it is a feeling of belonging. Reading Burnt Shadows felt like walking through the exhibits of the museum.

In August I was at the tail end of the Masters degree that had brought me to the UK. My lease for my little student accommodation in Brighton was almost up and I was preparing for the big move to London. The next few months would decide my future, my career, and where I would live for the foreseeable future. As I write this today, I am still in that place of uncertainty. The one thing that has changed is that I have a better understanding of what home means. It’s not brick and mortar, nor is it a country. It is trying to find peace, people that you can surround yourself, rituals that keep you rooted (video calls with my parents), and I don’t think I would have survived the last few months if it had not been for me finding a notion of home in my fragmented, ulta-pulta, and confusing life in London. Shamsie seems to be saying just that in Burnt Shadows, Home Fire, as well as, A God in Every Stone.

If Shamsie’s writing is the strongest when she explores the questions of home, belonging, and identity, her writing is the most endearing when she writes about families. The Tanaka/Ashrafs and the Burtons make for a strange family, but, despite not having any blood relations, that’s what they are. The lives of each member of this family is entwined intrinsically with those of the other. Hiroko is drawn to Elizabeth in India, she finds love and comfort with Sajjad, Sajjad survives in Pakistan because of Hiroko, Harry is compelled to visit his old Urdu teacher, Raza hero worships Harry and then when he falls from the pedestal changes his life’s course because of him, Elizabeth welcomes Hiroko into her house for a second time, Kim risks it all to help a stranger because of Raza, even though she has never met Raza herself. In many ways, Shamsie addresses the same question about how far is a person willing to go for family. The answer in this book seems to be to the world’s end.

At the risk of making a story too confusing, Shamsie’s novels comprise of multiple threads, intertwining and tangling with each other. Tug one thread and you can create an unsolvable knot. From the three books that I have read, I think her mastery lies in doing just that. The climax of her books are dramatic; the traits of her desi upbringing make themselves surprisingly obvious. She brings all the threads together to an explosive, heartbreaking end. Readers can scoff at it, I know some think that the last 20 pages of Burnt Shadows feel forced just to reach the end she wants. However, I am of the opinion that the novel was effective for me and it will stay with me for years to come because of its end. I found myself breathlessly turn the page even though a part of acknowledged that the climax was more cinematic than a work of literary fiction needed it to be. After closing my copy of the book I had to sit with my thoughts for several minutes because I remember feeling the helplessness as acutely as if it was happening to me. To be able to inspire these feelings through words is truly a triumph.

How to explain to the earth that it was more functional as a vegetable patch than a flower garden, just as factories were more functional than schools and boys were more functional as weapons than as humans. (Burnt Shadows)

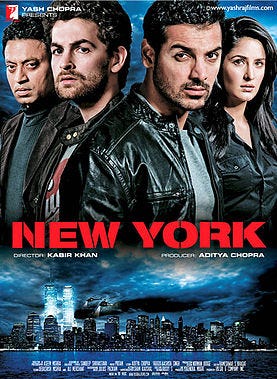

There is a scene in the movie New York that will stay imprinted in my brain for my entire life. John Abraham’s character is detained in a post-9/11 New York and questioned for daring to be Muslim. As part of the procedure he is closed in a metal box, so small that there is no where for him to move. The camera focuses on the disbelief and horror on his face, as he lies in a foetal position, naked, and waits for his fate to change. The claustrophobia can be felt through the screen. There is a scene in Burnt Shadows that stirred the same feelings in me; Raza travelling at the bottom of a boat, lying on top of bodies stuffed like sardines surrounded by human filth and cries of lament. It made me want to stop reading the book. It made me furious at the world for allowing these circumstances. How desperate do people have to be to endure these conditions? How horrible does home have to be if this is better than living there? As we witness a genocide, and watch as world leaders don’t bat an eye, I am going to leave you with the questions about global politics and its personal impact that Shamsie raises in her works.

Laughing, he said, “Cancer or Islam—which is the greater affliction?” (Home Fire)

This has turned into an essay rather than the simple review that I started writing. But Shamsie is one of those authors who I can read over and over and still find something new to appreciate, an idea that I had not noticed the first time, or a symbolism that I did not understand then. My hope is to read all her works, including her latest, Best of Friends, and then analyse her bibliography as a whole. One day I will make that happen, but for now I think I might pick up my copy of Home Fire and read through it once again. Maybe this time I will find a new meaning of identity, belonging, family, or home.