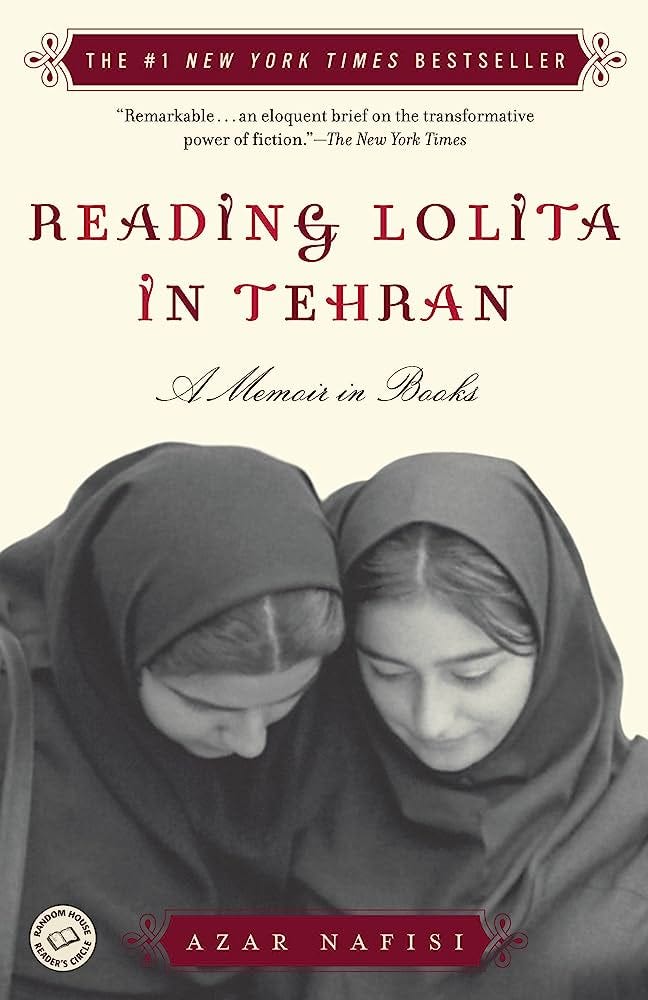

Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi

Genre: Memoir

Rating: 4 stars

“Every fairy tale offers the potential to surpass present limits, so in a sense, the fairy tale offers you freedoms that reality denies.”

I picked this book at a library sale in my college, and while I was doing that, a classmate mentioned that she didn’t enjoy the book. Apprehensive at first, I still bought the book (frankly, who can resist buying second-hand copies of hardbound books), but that unfavourable review did make me wait a while before I started reading it. During this lockdown, as I tried to make a dent in my huge tbr-pile, I decided to finally read the book. Two chapters in, I was reminded once again how two people could have such different experiences with the same book and how much of an impact timing can have on one’s reading experience. If I had read this book at any other, I may not have enjoyed the slow-paced and reflective memoir as much as I did.

“We in ancient countries have our past—we obsess over the past. They, the Americans, have a dream: they feel nostalgia about the promise of the future.”

Reading Lolita in Tehran is ‘a memoir in books’ by Azar Nafisi, Ph.D, an Iranian professor. But the book is so much more than that. It is also a memoir of a revolution, the story of a country and its women and an exploration of fiction, its impact on society and society’s impact on it. The book starts out as the story of the classes Nafisi conducted in her own home after she left her job as a professor at the university. It goes on to talk about her experiences of teaching the works of great literary minds like Nabokov, Fitzgerald, Austen and James while exploring what it means to read these works in a country torn because of an ideology. It is also about the Islamic Revolution in Iran and how the rise of the Ayatollah changed life for the women in the country. An important and interesting aspect of this change that Nafisi delves into is: what is more difficult, losing the rights that you have or not knowing what it means to have those rights at all?

“This is Tehran for me: its absences were more real than its presences.”

I can see why a lot of people may not enjoy the book. The book consists mainly of Nafisi’s dissection and thoughts about the books that she teaches at University and then later in her class/book club. But hidden in these analyses is the story of how each book that she reads and teaches connects to the changing world that they are living in. As the revolution changes day-to-day life for the men and women of the country, Nafisi attempts to understand her situation through fiction. She looks at the heroines of books like Lolita, Pride and Prejudice, The Great Gatsby, Daisy Miller, etc., and compares them to the women she is surrounded by. The book also explores the extent of moral policing of fiction and brings to the forefront the question: can these books be judged on the basis of the moral codes imposed on them?

“Do not, under any circumstances, belittle a work of fiction by trying to turn it into a carbon copy of real life; what we search for in fiction is not so much reality but the epiphany of truth.”

The book also explores the comfort and solace that one can find in stories. Nafisi’s recollections of withdrawing into books while her city is under attack are scary and relatable. After all, isn’t that what a lot of people are doing in these times of uncertainty, looking to books for answers and comfort? The book gives us a cast of female characters, different in not only their looks and backgrounds but also their ideology and way of living. Through their discussions about the books that they are reading, Nafisi gives us an insight into the restricted life women led during the revolution. Her exploration of the rules and regulations imposed on women, the inability to rebel against them and the suffocation they felt because of them were exceptionally intertwined throughout the story. Some of the incidents related to the story of all that she and the women around her had to endure were difficult for me to even imagine. She questions the love for home when it is no longer the home you recognise, the life we lead and the one we build for ourselves in our heads and the extent to which one can run away from one’s past. We end the book with Nafisi set to move to the United States of America, where she currently lives, and in that departure, she talks about what it means to leave her people behind.

“You get a strange feeling when you're about to leave a place, I told him, like you'll not only miss the people you love, but you'll miss the person you are now at this time and this place because you'll never be this way ever again.”

To me, the book was a reminder of how comforting fiction can be and how literature has the ability to transcend time and borders, creating parallels and making it possible to understand the world we live in. “[A] novel is not moral in the usual sense of the word. It can be called moral when it shakes us out of our stupor and makes us confront the absolutes we believe in.”