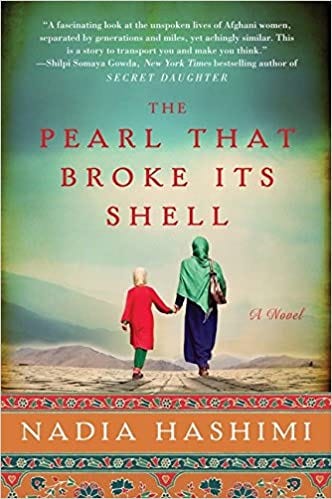

The Pearl That Broke Its Shell by Nadia Hashimi

The Pearl That Broke Its Shell

Author: Nadia Hashimi

Genre: Historical Fiction

Date: 17 September 2021

Rating: 3 stars

Review: My bookshelf is filled with books by white authors about white characters living in white countries. I came to this realisation sometime last year after reading an article about decolonising our bookshelves. It is not that I reach out to any particular books because they are by authors from America or Britain, it just happens subconsciously. Well, to be frank, it happens because of the amount of publicity and marketing these books receive. While I do read books by Indian authors pretty often I have sadly read very few books written by authors of different nationalities. I tried to change that last year by reading one book a month by authors from a country I hadn’t read before. I was successful but I realised it didn’t even make a dent in the number of countries I should be reading from.

So earlier this month I opened an alphabetical list of all the countries in the world on my laptop and decided to make my way through the list, reading one book from every country, preferably by a woman but that isn’t always possible. I don’t know how long that’s going to take me because if you don’t know there are a really crazy number of countries in this world and your girl is not the fastest reader but this book was a start. Since we cannot travel, thanks to Ms Rona, I am going to travel from the comfort of my bed and read books from around the world. So I am going ahead and christening this challenge: Around The World In Books.

I read The Pearl That Broke Its Shell by Nadia Hashimi, a book by an Afghan-American author set in Afghanistan, this month. It is rare for me to read books in a timely manner. I generally get around to reading the hyped books of the year in the following year. I got around to reading books from the lists that were published to support the #BlackLivesMatter movement a month later. But this book could not be more relevant.

As women in Afghanistan dress up in colourful clothes to fight for their identity, reading this book about the stories of two women in Afghanistan facing very similar struggles during two different stages of the country’s history felt surreal because here we are witnessing the cycle repeat itself. The Pearl That Broke Its Shell is written in alternating chapters, one that follows Rahima at the beginning of the 21st century and the other follows her great-great-grandmother Shekiba at the beginning of the 20th century.

Rahima has four sisters and no brothers. In a society where having a male heir is of utmost importance for every family, this is a sorry state for her family. Rahima and her sisters can only sporadically attend school. Her opium-addicted father is constantly pressured to get home another wife who will be able to give him a son. And her mother is shamed for her inability to fulfil her duty to her husband and family. Following the advice of her sister, Rahima’s desperate mother decides to follow the tradition of bacha posh. Turning Rahima into a bacha posh involves dressing her in clothes borrowed from her male cousins, cutting off her hair and calling her Rahim. For all purposes, Rahima becomes her father’s son, taking on additional responsibilities and running errands her mother and sisters can’t. This comes with freedom for the little girl that she hadn’t dreamed of before. She gets to attend school, kick a ball around with her friends and be excused from household chores so she can be a child for the first time in her life. But when her mother continues the bacha posh for longer than is advised it invites trouble that will not only take away Rahima’s freedom but also have drastic consequences for her sisters.

As Rahima is thrust into a world of sister-wives, household responsibilities and motherhood, all the while scared of the looming presence of her war-lord husband, she seeks comfort in the stories of her great-great-grandmother Shekiba told to her by her aunt. Divided by a century, there are parallels to be drawn between their lives because Shekiba too became a man when it was required of her. After being orphaned and mistreated for her burnt features, Shekiba has to resort to her own strength and ability to become a man when the occasion called for it to survive and escape situations that are dark and horrible.

I thought the topic was really interesting. The custom of bacha posh and the questions it raises in the mind of a child, in a world where gender norms are drilled into minds so early on, was a discussion that I really was absorbed by. The story touched me in its depiction of the life women in Afghanistan lived, right from Raisa, Rahima’s Madar-Jaan’s, turmoil after losing her daughter, to Khala Shaima, Parwin and Shekiba’s struggles with a society so disgusted by disfigurement and disability, to Benafsha’s sacrifice for love, every woman in this book is a depiction of the struggle that women have to face just to survive in this world. There are parts of this book that broke my heart. The Pearl That Broke Its Shell comes with trigger warnings for a lot of things including violence, sexual assault, miscarriage and childbirth, suicide and torture. It is about all these things but the book is also about clinging to hope when the world seems desolate and working to change your naseeb because that is the only way to escape the cycle. Along with all this, it is also a tale of the changing climates within a country during the course of Afghanistan’s history.

While the themes of the book were just the thing I was looking for, the execution did not meet my expectations. The book could have done with some editing to remove parts of chapters that felt repetitive and droned on. It would have been a much faster and engaging read if it had been about 50-75 pages shorter. The writing style was a little simplistic, which I am not complaining about, but it failed to really bring out the emotions that I should have been feeling while reading about the turmoil in these pages. There are comparisons drawn between this book and Khaled Hosseini’s work and I can see why the story itself is quite reminiscent of The Thousand Splendid Suns, but while Hosseini has this way of almost forcing you to feel sad (The Kite Runner, I am looking at you) this book missed the mark. I felt detached from the characters and their situation, like a third party looking in on the incidents of the story instead of being immersed, and so, even though I was rooting for them, it was a little difficult to experience their pain.

But, overall, reading this book was a fulfilling experience and the first step towards completing this strange and seemingly impossible task I have set up for myself. Let’s hope I keep at it and at least finish a respectable bit of it by the end of the year.